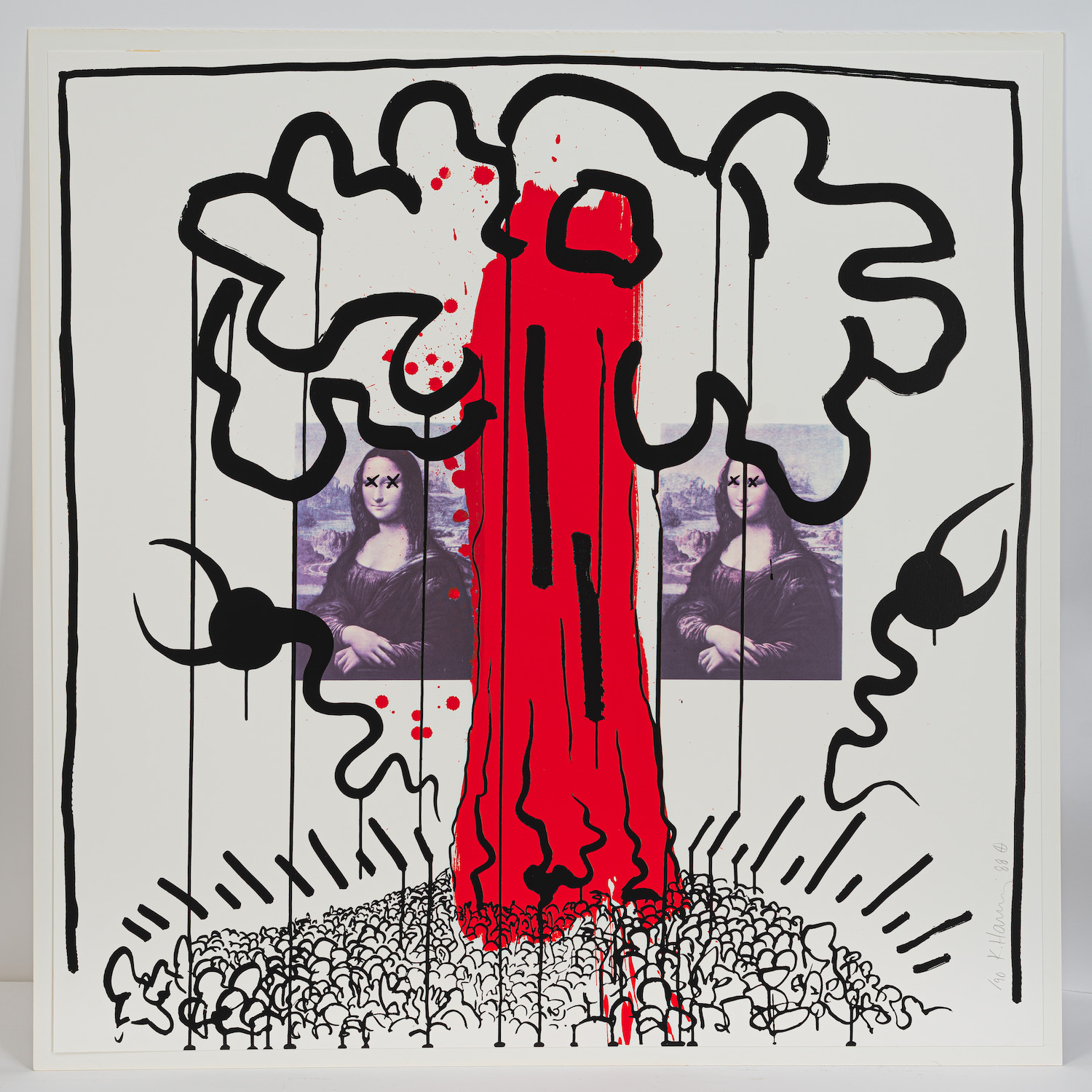

In the latter stages of Keith Haring’s life, his artistic vision took a decidedly somber turn in the Apocalypse series: his profound collaboration with literary figure William S. Burroughs. The series, a set of 10 screenprints, unfolds as a visceral response to the AIDS epidemic, which Haring himself was diagnosed with in 1988. This haunting collection reflects the fear, despair, and contemplation faced by many during this time, offering a raw depiction of life, death, religion, sexuality, and the societal response to the epidemic.

The first print in the Apocalypse series was inspired by, and reflects the following excerpt by William Burroughs:

Page 4

The household appliances revolt: washing machines snatch clothes from the guests, bellowing Hoovers suck off makeup and wigs and false teeth, electric toothbrushes leap into screaming mouths, clothes dryers turn gardens into dust bowls, garden tools whiz through lawn parties, impaling the guests, who are hacked to fertilizer by industrious Japanese hatchets. Loathsome, misshapen, bulbous plants spring from their bones, covering golf courses, swimming pools, country clubs and tasteful dwellings.

Keith Haring’s Apocalypse series, as the name suggests, traverses the realms of the eschatological. Burroughs, renowned for his “cut-up” technique of fragmentation and reassembling texts, contributes the text pages printed on acetate film to accompany the artworks. These juxtaposed words and phrases accentuate the oscillating emotions of dread and fleeting euphoria, creating a compelling narrative that underpins Haring’s visual contributions. This method of blending disparate elements to create fresh meanings, influenced heavily by Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s The Third Mind, had previously captivated Haring at the Nova Convention in 1978.

In his pieces, Haring interweaves stark Christian symbolism, such as a bleeding heart Christ, with images borrowed from 1950s advertisements and elements of Catholic theology. The intertwining of religious iconography and consumerist symbols – from depictions reminiscent of Dante Alighieri’s Inferno and Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights to magazine clippings from Haring’s own infancy – captures the conflict of the times. Particularly poignant is an image of a mother from an American magazine ad, evocative of the Madonna, leaning over her baby.

Further melding of cultural and religious symbols emerges in the follow-up collaboration, “The Valley.” The suite of etchings manifests a male torso performing a self-inflicted stigmatization, reflecting not only the physical affliction of the AIDS crisis but also a profound spiritual anguish. Such intense engagement with Catholic imagery draws parallels between Haring and other contemporaneous icons: Robert Mapplethorpe, Andy Warhol, and the ever-rebellious pop star Madonna. For these artists, the Catholic faith provided a rich tapestry from which to draw, critique, and rebel.

Beyond the stark religious undertones, images of computers, spermatozoa devils, and modern machines intersect with halos, stigmata and divine illuminations. These icons serve as emblematic of the age’s complexities, struggles, and dualistic perceptions. As Timothy Leary, the proclaimed guru of the acid age, astutely observed, the Apocalypse series felt as if “Dante and Titian got together.”

The Apocalypse series does more than just chart the societal and personal terrain of a challenging epoch. It stands as a testament to Haring’s and Burroughs’ ability to transcend conventional artistic boundaries, merging visual and textual mediums. Through this, they not only chronicled the tribulations of the AIDS epidemic but also illuminated broader societal issues, their work resonating deeply in a world grappling with both generational and global challenges.